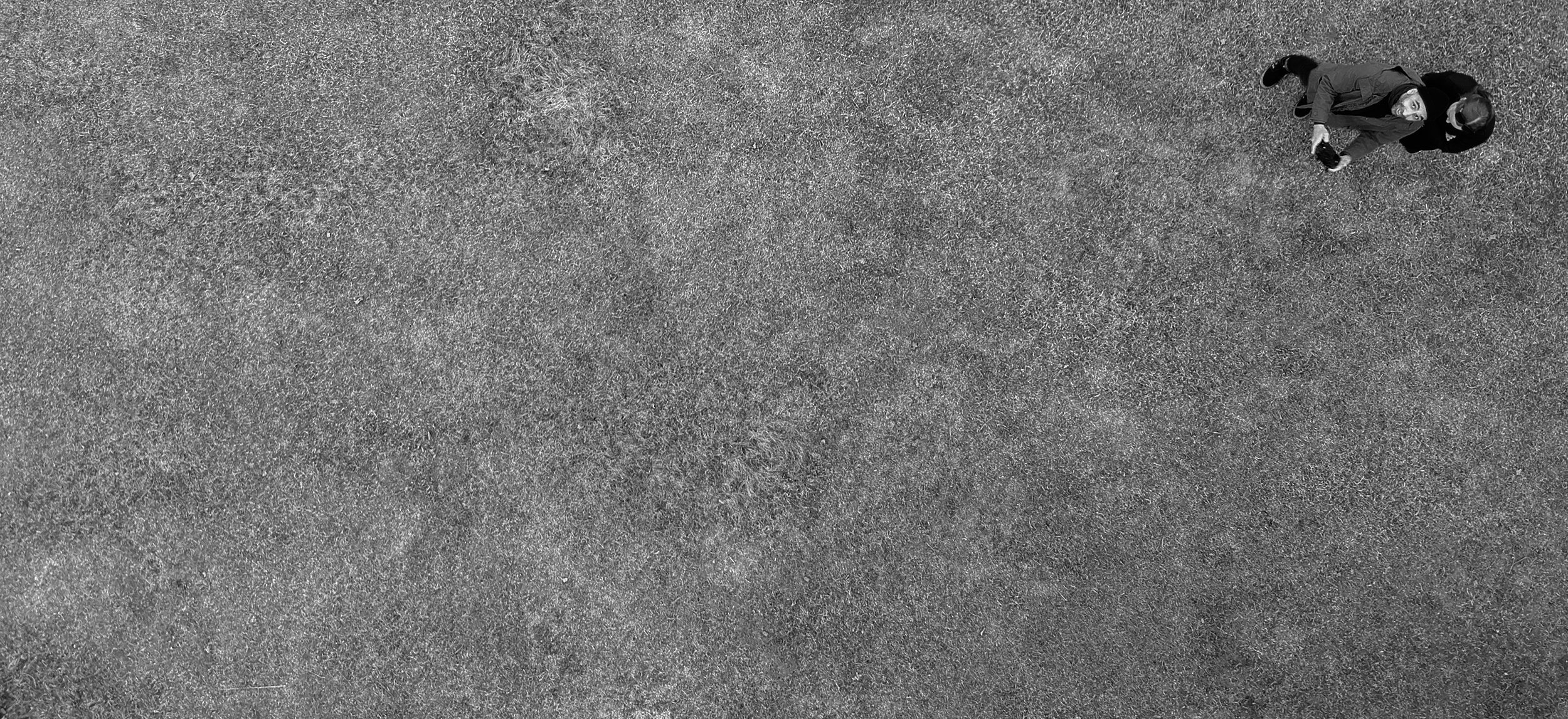

No Gravity, 2019

Statement

Computing Aesthetics"In the future, the only artwork that will survive will have no gravity at all."

– Nam June Paik, Random Access Information¹

I use the computer as a medium, recognising its inherent capacity for computation rather than mere manipulation. Inspired by the mentorship and legacy of Gérard Pelé, who supervised my work at the Centre de Recherche sur l'Image of the Université de Paris 1, Panthéon-Sorbonne, I delve into Computing Aesthetics, a domain that merges art with the computational domain. My artistic exploration explores the profound impact of speed on human existence, echoing Paul Virilio's concept of Dromology, which questions the influence of velocity on society.

I started making generative work around 1996 using the C language. Although I used a Roland XYZ Pen Plotter under the supervision of Pelé at the Laboratoire de Psychophysiologie de la Perception (Institut d'Esthétique et des Sciences de l'Art), it is the pivotal encounter with artist Vera Molnar that left an indelible mark on my journey. Molnar's generous gesture of offering me plotter pens and ink resonated deeply, establishing a connection with the art of early computer works, akin to Molnar's own. This legacy transmission fueled my creative expression, prompting me to produce subjects steeped in frugal line work, reminiscent of Molnar's pioneering artworks.

My artistic exploration delves into the historical confluence of photography, aviation, and computing, all of which have played significant roles in shaping the trajectory of warfare. Embracing Sun-Tzu's assertion in The Art of War that speed remains intrinsic to conflict, I trace the parallel developments of cameras and airplanes during World War I, culminating in the birth of aerial photography. Subsequently, the emergence of computers facilitated the creation of the devastating atomic bomb during World War II. Today, the convergence of airplanes, cameras, and computers has spawned the drone, the ultimate tool of modern warfare.

In my recent works, I try to harness the power of words as a fundamental element. Employing the Divide and Conquer algorithm, I invite the viewer to contemplate the inherent meanings of sentences merely perceptible, drawing parallels with Merleau-Ponty's The Visible and The Invisible. This journey invites audiences to question the conspicuous surface and probe deeper into the hidden implications of language and communication.

My exploration of aerial aesthetics encompasses themes of surveillance, stealth, and precision. In Surgical Geopolitics, I contemplate the moral dilemmas inherent in making life and death decisions within drone warfare. Through the work titled Rainbow Warrior, I question the use of colours as codenames for weapons, unearthing the concealed atrocities behind seemingly innocuous names. Colours, laden with diverse meanings and emotions throughout history, take on a sinister connotation within the context of war and devastation. In an age when speed is a defining characteristic of our existence, the microprocessor becomes a lens through which we can glimpse the intricate folds of reality and perception.

— Moe Louanjli, July 2023.

¹ Nam June Paik, Random Access Information part of the Video Viewpoints series, curated by Barbara London, at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 25, 1980.

During our conversation, Molnar and I discussed BASIC programming language, which she used to make her art, as well as CalComp plotters and BFM computers. At the end of our visit, Molnar generously gifted me a box of plotter pens of various brands and some Rotring ink, tools that would profoundly shape my own artistic journey.